People love brainstorming blue ocean ideas, coming up with unique ways to create their own uncontested market space, and doing it so well they can make competition irrelevant. These sessions can open up business minds that might be stuck. They can get your people out of their usual thinking so they can explore where else you could go. However, if you feel like your brand is sailing the open seas all by your lonesome, think again. In any market situation, if these blue ocean brands steal money from another brand, they will figure out who took it and come after you.

Suddenly, your blue ocean brand is playing in a red ocean, filled with bloody battles to the death of one brand over the other. Even though you might be significantly better than the brand you are fighting, it will be challenging. Make sure you are ready for battle. Think about competitive strategy, as it might get bloody.

Blue Ocean

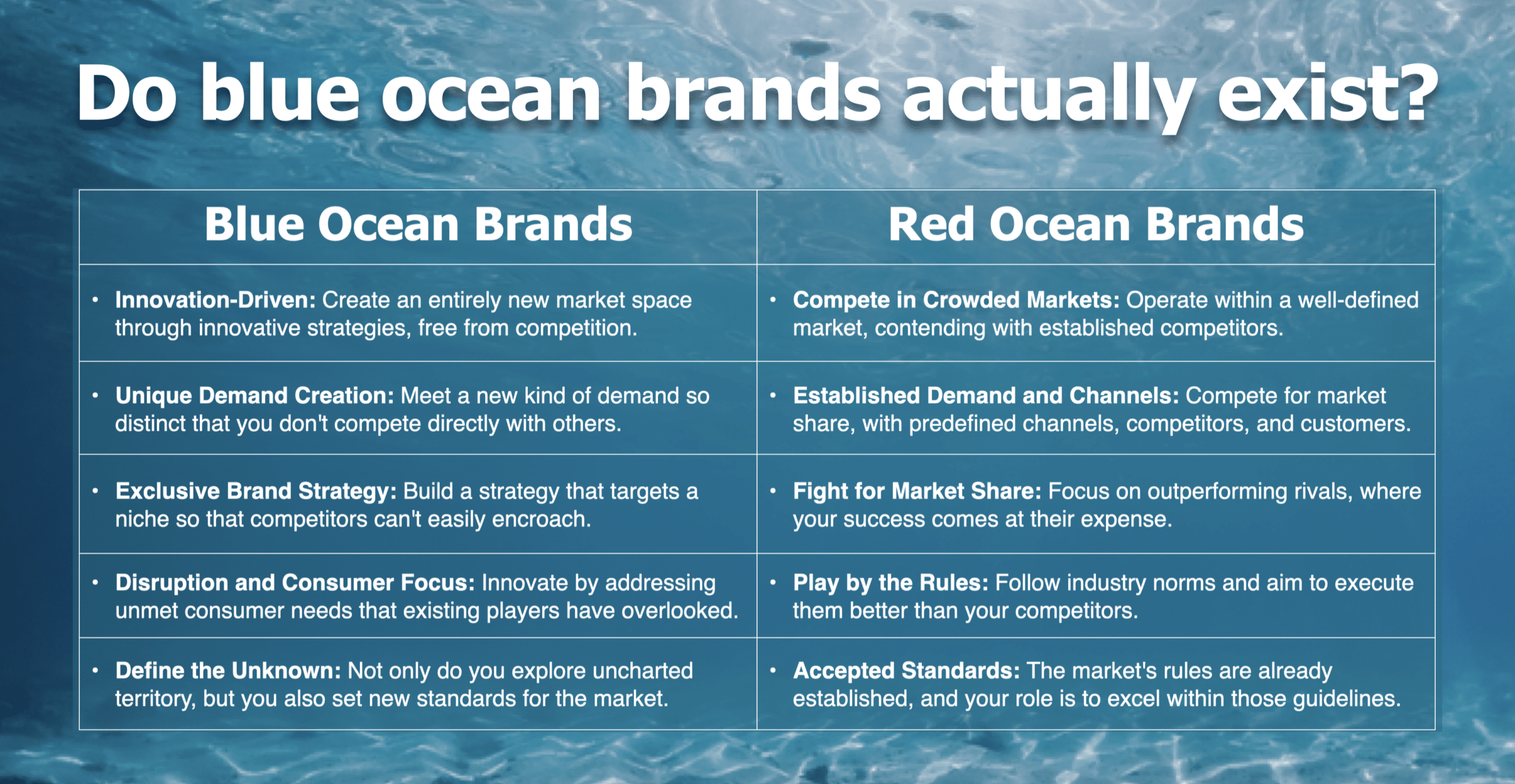

Blue ocean strategy, introduced by Professors W. Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne, revolves around the idea of creating innovative market spaces where competition is irrelevant, often by addressing a new demand that others have overlooked. In contrast to red oceans—crowded markets defined by intense rivalry—blue oceans allow companies to carve out their own niche, free from direct competition. In these spaces, companies can enjoy strong growth and profitability, as they create rather than compete. 🚀💼

However, while the blue ocean concept is appealing, true blue ocean opportunities are not only rare but can also be short-lived. As a company succeeds in creating a new space, competitors inevitably emerge, turning the once uncontested market into a battleground—a red ocean. Identifying blue ocean opportunities requires a deep understanding of the market, continuous innovation, and the agility to evolve with consumer needs. ⚡🧩

That said, blue ocean strategies are far from mythical.

Some companies have effectively crafted new market spaces, challenging industry norms and achieving extraordinary growth. Think of Apple’s iPhone, Cirque du Soleil, or Tesla—brands that didn’t just compete, but transformed their industries through innovation and a unique value proposition.

The secret to finding blue ocean opportunities lies in nurturing a mindset focused on growth and creativity. Businesses must rethink traditional market boundaries, redefine their target audiences, and prioritize value creation over mere cost-cutting. Those that can strike this balance will stand a better chance of discovering and thriving in blue ocean spaces.

In conclusion, while blue ocean opportunities may be scarce, they do exist for companies willing to innovate, take risks, and challenge the status quo. Pursuing blue ocean strategies encourages businesses to think differently and drive creativity, paving the way for long-term success in an ever-evolving landscape.

To illustrate, click on the blue ocean brand strategy diagram to zoom in.

Brand Strategy

Murder and strategy have one thing in common; they both start with opportunity.

Finding those blue ocean strategies can create opportunities. The reality is that most brands play in a highly competitive space. Every gain you make comes at the expense of someone else, who is also always trying to win.

- Netflix has dramatically impacted network television and movie theatres.

- Uber is experiencing fights across North America with Taxi companies, and Municipal governments.

- Amazon is fighting against retailers and brands selling direct.

It’s fine to use a blue ocean brainstorm to create these types of ideas. You have to use a red ocean defense to run these businesses. Anytime you take a dollar away from someone, they will fight back.

How to win in a red ocean world

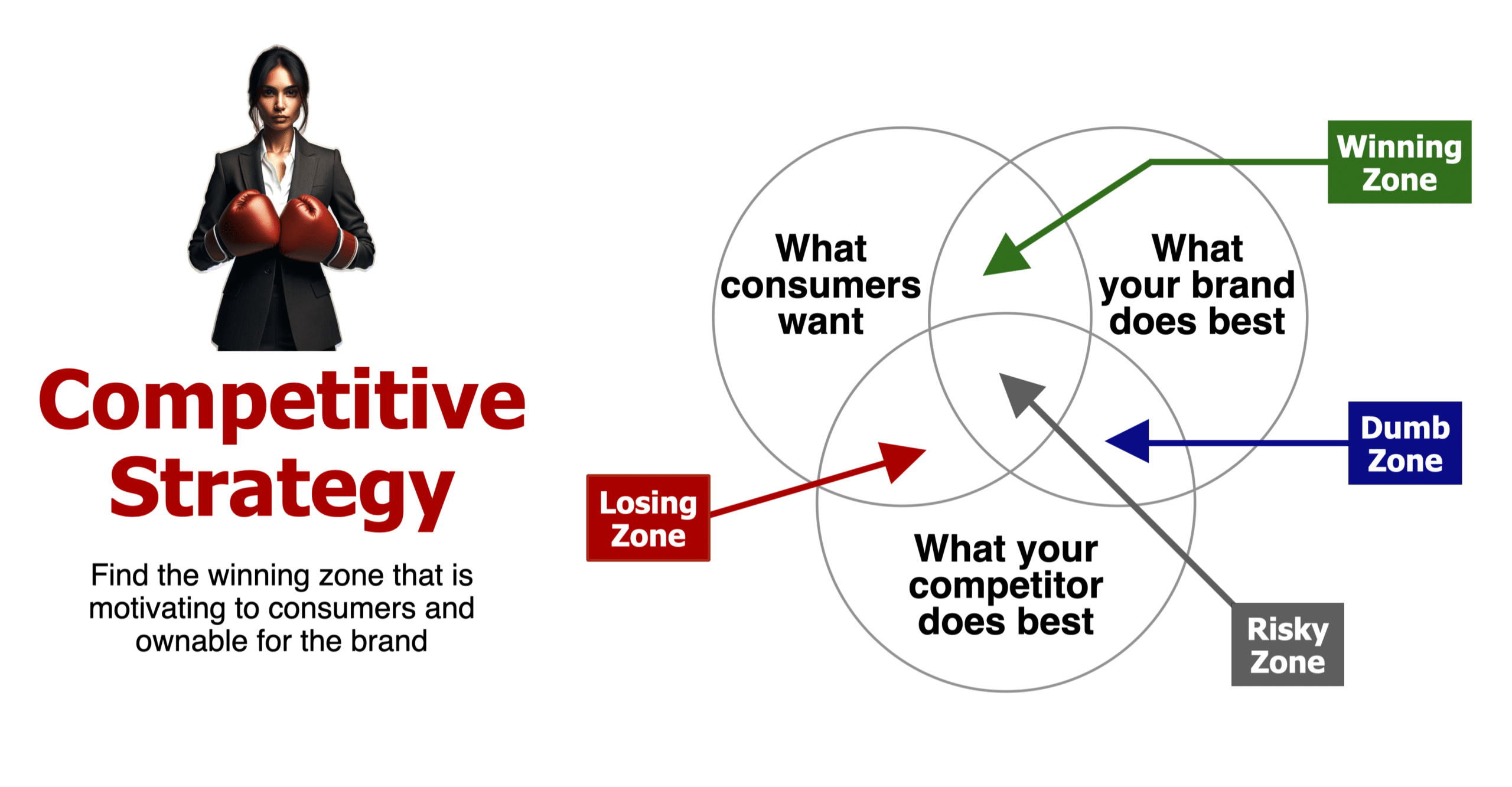

Brands have four choices: better, different, cheaper, or not around for long. To find the competitive space in which your brand can win, I introduce a Venn diagram of competitive situations that we will use throughout this discussion.

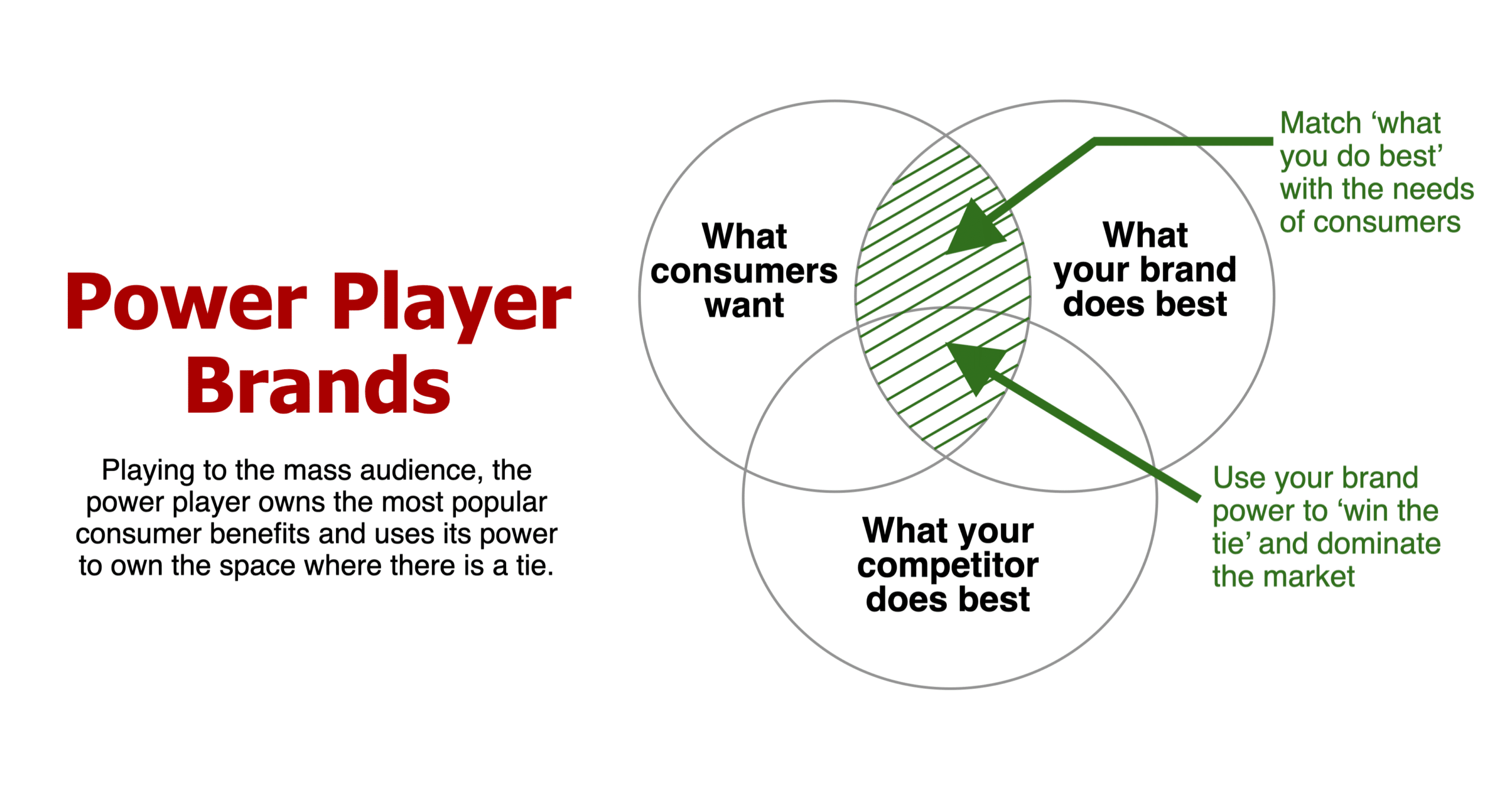

You will see three circles. The first circle comprises everything your consumer wants or needs. The second circle includes everything your brand does best, including consumer benefits, product features, or proven claims. And, finally, the third circle lists what your competitor does best.

To illustrate, click on the blue ocean brand strategy diagram to zoom in.

Find the winning zone.

Your brand’s winning zone (in green), is the space that matches up “What consumers want” with “What your brand does best.” This space provides you a distinct positioning you can own and defend from attack. As a result, your brand must be able to satisfy the consumer needs better than any other competitor can.

Your brand will not survive by trying to compete in the losing zone (in red). This space matches the consumer needs with “What your competitor does best.” When you play in this space, your competitor will beat you every time.

As markets mature, competitors copy each other. It has become harder to be better with a definitive product win. Many brands have to play in the risky zone (in grey), which is the space where you and your competitor both meet the consumer’s needs in a relative tie.

There are four ways you can win the risky zone:

- Use your brand’s power in the market to squeeze out smaller, weaker brands.

- Be the first to capture that space to earn a reputation you can defend

- Win with innovation and creativity to make your brand seem unique

- Build a deeper emotional connection to make your brand seem different

Sadly, I always have to mention the dumb zone (in blue) where two competitors “battle it out” in the space consumers do not care. One competitor says, “We are faster,” and the other brand says, “We are just as fast.” No one bothered to ask the consumer if they care about speed. Both brands are dumb.

Competitive Strategy

Regarding the competitive strategy, you must choose from one of four different types of competitive situations you find your brand operating within. The power players are the dominant leader in the category and take a competitive defensive stance. And, the challenger brands have gained enough power to battle head-to-head with the market leader. The disruptor brands have found a space so different they can pull consumers away from the significant category players. Moreover, craft brands aggressively go against the category with a niche target market and a niche consumer benefit. They are small and stay far away from the market leaders.

Brands rarely experience competitive isolation. Even in a blue ocean situation, the euphoria of being alone quickly turns to a red ocean, cluttered with the blood from nasty battling competitors. The moment we think we are alone, a competitor is watching and believing they can do it better than we can. When you ignore your competition, believing only the consumer matters, you are on a naive pathway to losing. Competitors can help sharpen our focus and tighten our language on the brand positioning we project to the marketplace.

Four types of competitive brands:

- Power players

- Challenger brands

- Disruptor brands

- Craft brands

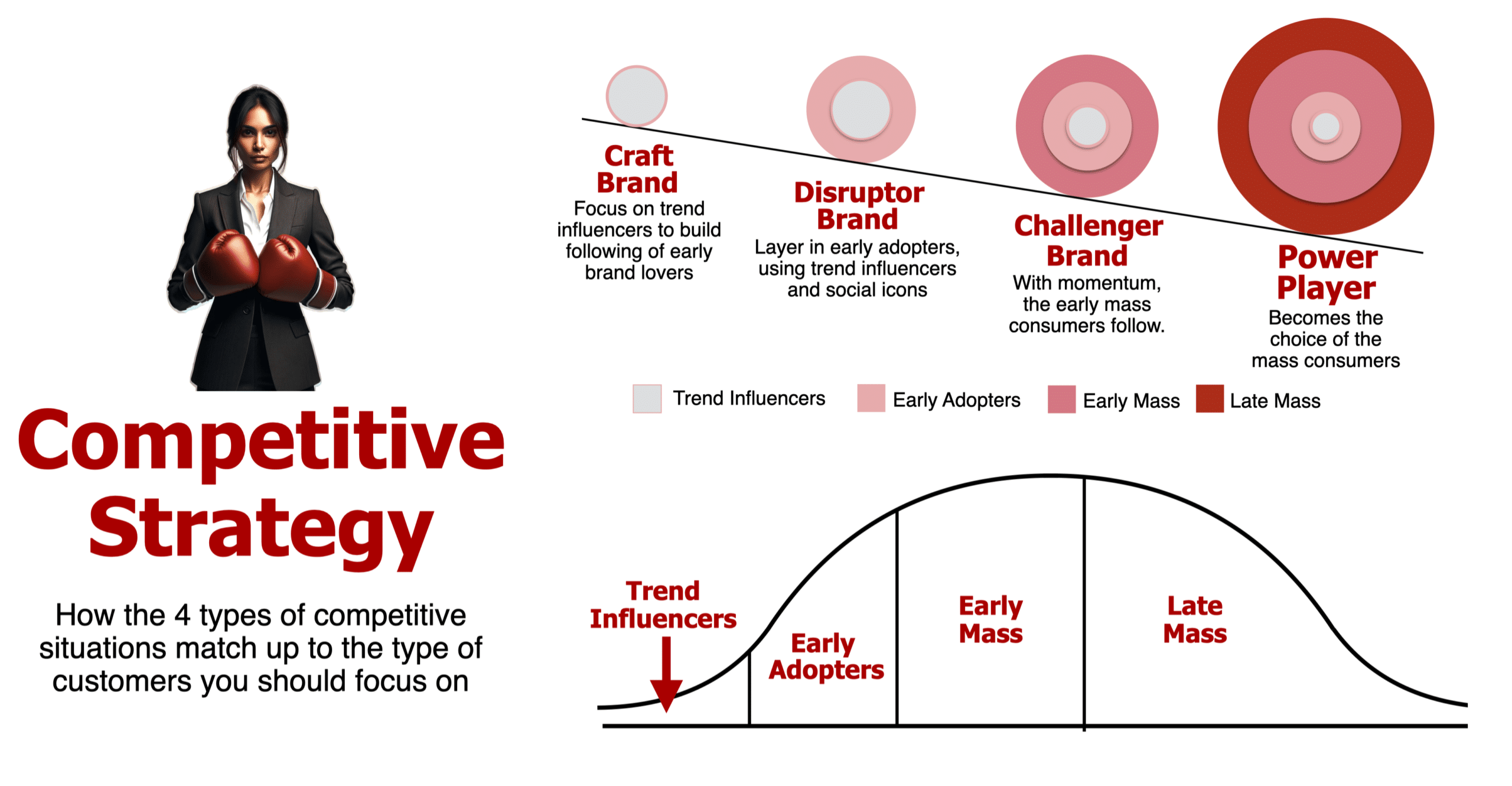

Using the innovation curve to look at the 4 types of customers

Below is an image that helps explain the competitive brand situations. The curve at the bottom of the chart represents the typical adoption curve in which customers can be segmented based on their willingness to try new products or adopt new trends. It visually aligns each type of brand strategy with the consumer group most relevant at each stage of growth.

- Trend Influencers: Innovators, the first to adopt

- Early Adopters: Those who follow trends closely but wait to see some initial success

- Early Mass: Consumers who begin to purchase once the product is more widely accepted

- Late Mass: The largest and most risk-averse group, which adopts after the product has become mainstream

This framework is designed to help businesses understand where they are in their brand evolution and identify the customer groups they should prioritize to drive growth.

To illustrate, click on the blue ocean brand strategy diagram to zoom in.

The Competitive Strategy image above illustrates the 4 types of competitive brand strategies and how they align with different stages of consumer adoption, providing insight into which customer groups brands should prioritize at each stage of growth:

Craft Brand:

Target Audience: Trend Influencers

- At the initial stage, brands focus on building a small but dedicated following of trend influencers. These are the early, passionate adopters who can help generate buzz and credibility around the brand. By appealing to this niche group, a brand can establish itself as a unique and exclusive option that stands out from the competition.

Disruptor Brand:

Target Audience: Early Adopters

- As the brand gains traction, it transitions into the role of a disruptor by expanding its appeal to early adopters. This stage involves using social icons and trend influencers to maintain momentum and expand the brand’s reach. Disruptor brands leverage their innovative or differentiated value propositions to convince a larger, yet still selective, group of consumers to buy into their offering.

Challenger Brand:

Target Audience: Early Mass

- With increased momentum, the brand begins to attract a broader audience—specifically the early mass market. At this point, the brand is no longer just a niche or disruptive entity but starts to challenge the established leaders by appealing to a wider consumer base. This phase is critical for building market share and brand awareness, as the early mass follows the lead set by trend influencers and early adopters.

Power Player:

Target Audience: Late Mass

- Once the brand has established a strong position, it becomes a “Power Player” in its category. In this stage, the brand becomes the go-to choice for the late mass of consumers, who often represent the majority of the market. These consumers are typically more conservative, preferring established, reliable brands. The focus here is on maintaining dominance and solidifying the brand’s status as the leader in its space.

Power player brands

Power players lead the way as the share leader or perceived influential leader of the category. These brands command power over all the stakeholders, including consumers, competitors, and retail channels.

Regarding positioning, the power player brands own what they are best at and leverage their power in the market to help them own the position where there is a tie with another competitor. Owning both zones helps expand the brand’s presence and power across a bigger market. These brands can also use their exceptional financial situation to invest in innovation to catch up, defend, or stay ahead of competitors.

Power player brands must defend their territory by responding to every aggressive competitor’s attacks.

They even need to attack themselves by vigilantly watching for internal weaknesses to close any potential leaks before a competitor notices. Power player brands can never become complacent, or they will die.

To illustrate, click on the blue ocean brand strategy diagram to zoom in.

One of the best contemporary power player brands is Google, which has managed to dominate the search engine market. The company’s extreme focus and smart execution gained market power and squeezed out Microsoft and Yahoo. Focused on providing knowledge for consumers, Google has continued to expand its services into a bundle of products with e-mail, maps, apps, docs, cloud technology, and cell phones.

Regarding advertising dollars, the combination of Google and Facebook now accounts for over 80% of all digital advertising spending. We are currently entering the digital duopoly age with influence shared between these two power player brands.

Blackberry: A failed power brand

On the other hand, BlackBerry is an excellent case study of a power player which forgot to defend its castle. In 2009, Blackberry dominated the B2B corporate smartphone market. Fanatics were so addicted they referred to the brand as “CrackBerry.” At the time, a great market research story on BlackBerry said, “If there were 20 people in the room and one had a BlackBerry, guess which one person was the boss.”

That is a great brand positioning space to own. However, BlackBerry became distracted by the Apple launch and tried to be more like Apple rather than staying true to itself. BlackBerry launched an inferior touchscreen phone, an undifferentiated tablet, sponsored rock concerts, and launched Blackberry Messenger (BBM) for young teens. The brand failed to attack itself, leaving severe product flaws, which frustrated their users. Pretty soon, corporations began to switch to the iPhone.

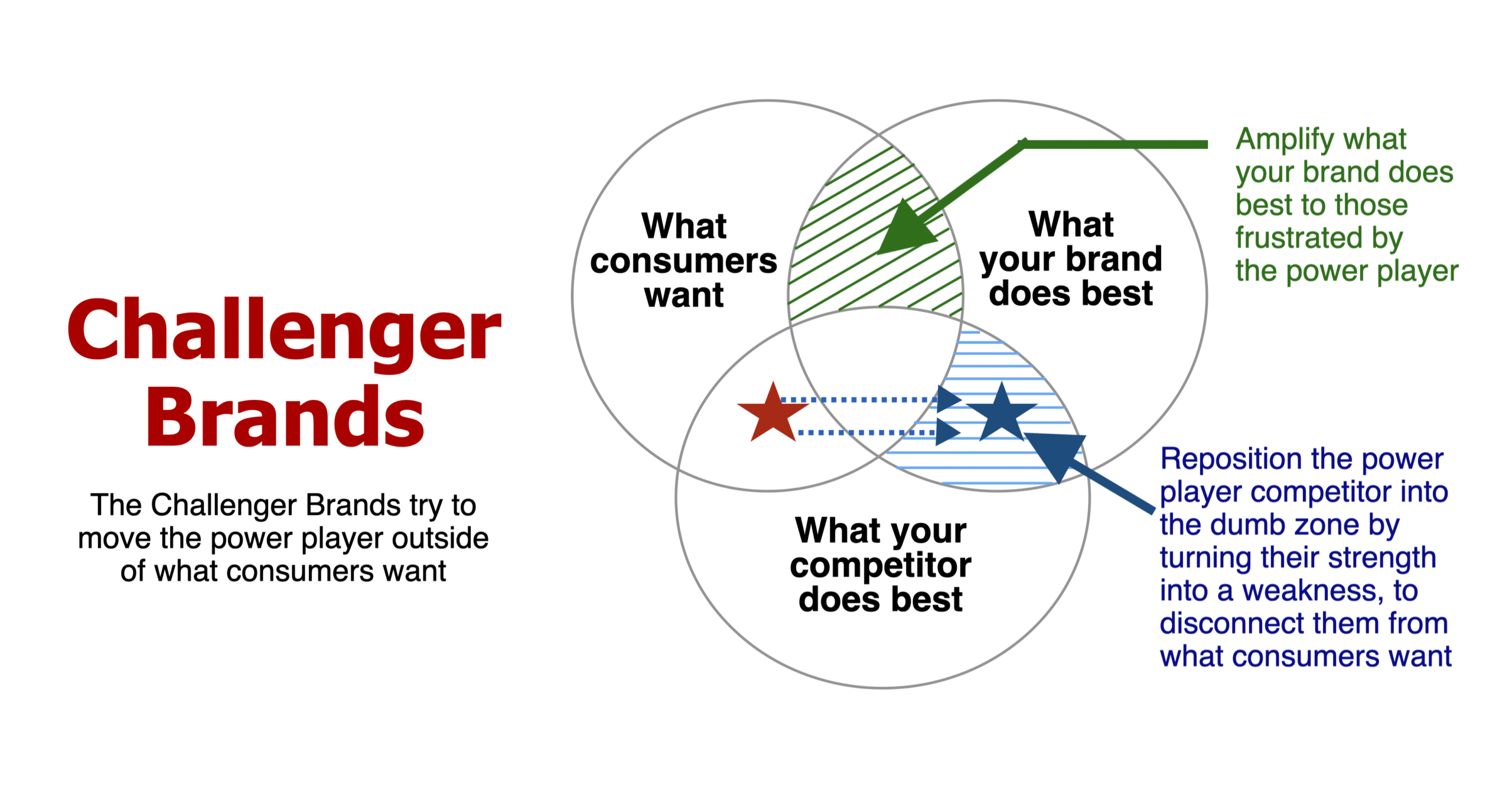

Challenger brands

Challenger brands must change the playing field by amplifying what your brand does best while simultaneously repositioning the power player brand you want to take down.

While your first instinct would be to attack the power player’s weakness, the smarter move is to reposition one of the power player’s well-known strengths into a perceived weakness. This strategy helps move the power player brand outside of what consumers want.

When you attack a power player brand, be ready for the leader’s potential defensive moves and anticipate a response with full force, as the power player brand has more significant resources than you. You also need to be highly confident that your attack will make a positive impact before you begin to enter into a war. The worst situation is to start a war you cannot win, as it will drain your brand’s limited resources, only to end up with the same market share after the war.

Since the power player leader tries to be everything to everyone, you can narrow your attack to slice off those consumers who are frustrated with the leading brand. Tap into their frustration to help kickstart a migration of consumers away from the leader. If you can gain these lost consumers, you can quickly change share positions.

To illustrate, click on the blue ocean brand strategy diagram to zoom in.

The Pepsi challenge

One of the best examples of a challenger brand that made significant gains is the Pepsi Challenge from the 1970s. It was a direct offensive attack on Coke. In blind taste tests, Pepsi was the preferred brand. Pepsi is a much sweeter taste, so in a quick hit, it was the chosen brand. Coke is an acquired and memorable taste. The blind taste test took away the Coke brand name and the emotional feelings of that brand. At the same time, Pepsi amplified its strength as the “new generation” and positioned the brand as the solution to consumers ready to reject the “old taste” of Coke. Pepsi’s approach on taste contributed to the launch of a sweeter “New Coke.”

Avis

Avis created the “We try harder” campaign that openly said “we are #2, so we have to try harder” which turned the strength of Hertz #1 market share into a slight weakness, making consumers wonder if the #1 brand Hertz was resting on its laurels. They layered in reasons to believe saying they couldn’t’ afford to provide unwashed cars, low tire pressure and dirty ashtrays which made consumers start to wonder if Hertz did those things.

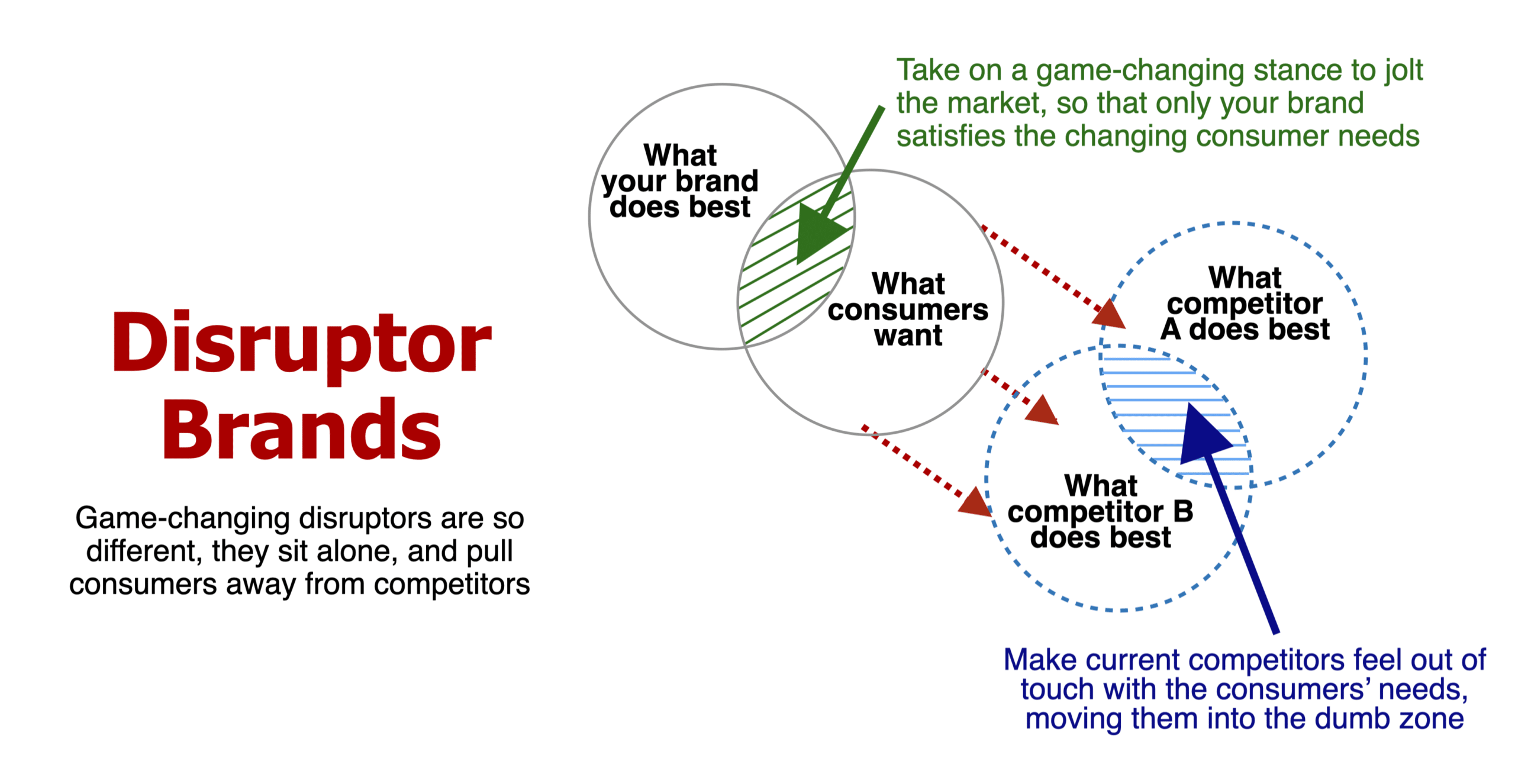

Disruptor brands

Disruptor brands move into a blue ocean space, all by themselves. They use a new product, distribution channel, target market or price point. They are so different they appear to be the only brand that can satisfy the consumer’s changing needs.

When successful, the disruptor brand repositions the significant players, making them appear unattached to consumers.

While everyone wants a game-changer, it is a high-risk, high-reward competitive situation. The trick is you have to be “so different” to catch the consumer’s attention and mindshare. Being profoundly different increases the risk you may fail. Also, your success may invite other entrants to follow. At that point, you become the new power player of the new segment. You have to continue attacking the significant players while defending against new entrants who attack your brand.

Technology examples

Uber, Netflix, and Airbnb are contemporary brands that effectively use modern technology to create such a unique offering that they cast significant category-leading brands or entire industries as outdated and outside what consumers want. Uber disrupted the taxi market, Netflix is revolutionizing the way we watch TV, and Airbnb has had a dramatic impact on hotels. These brands have a smarter ordering system, better service levels, and significantly lower prices.

To illustrate, click on the blue ocean brand strategy diagram to zoom in.

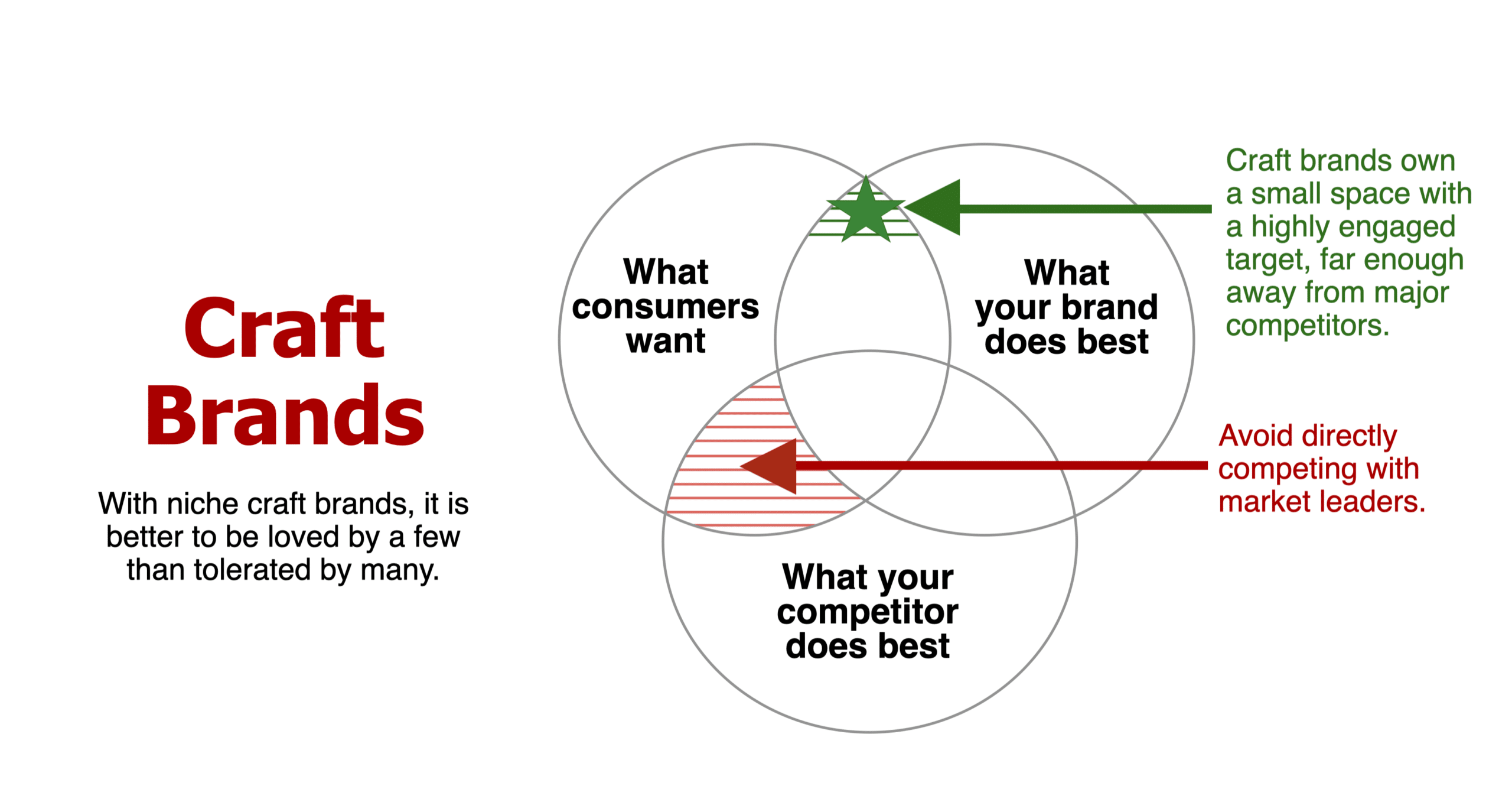

Craft brands

Craft brands must win a small space in the marketplace that offers something unique to a highly engaged target. These brands succeed when they are far enough away from significant competitors that the leaders ignore them because craft brands stay hidden away.

Craft brands build themselves behind a micro-benefit, including gluten-free, low fat, locally grown, organic or ethically sourced. These craft brands take an antagonistic approach to the rest of the category, portraying every other brand in the category as old-school, overly corporate, unethical, flawed in the manufacturing or the use of ingredients. Many times, these brands take a very aggressive marketing stance, calling out the other brands as unethical or stupid. Craft brands believe it is better to be loved by the few than liked or tolerated by many.

Five Guys

A fantastic of example a craft brand is Five Guys Burgers, which uses fresh, high-quality beef and a commitment not to begin cooking your burger until you order it. The portions are more substantial than typical fast food, and they charge super-premium prices. Five Guys have gone in the opposite direction to most fast-food restaurants, whose meals seem frozen and microwaved. Five Guys has expanded rapidly with word of mouth helping the brand earn a reputation as “the best burger.” Now that Five Guys has become a global brand, McDonald’s has to figure out an adequate competitive response.

Dollar Shave

Another excellent example of a craft brand is Dollar Shave, which launched as an online subscription model for razor blades. Dollar Shave uses smart sourcing and a direct-to-consumer distribution model. This efficient model eliminates costs and allows the brand to sell razors at a fraction of the cost you pay for Gillette. For consumers, the price of razor blades has gotten out of control, no matter how much innovation the leaders try to portray. Dollar Shave’s advertising openly mocked Gillette, yet it started in such a small niche, so Gillette ignored them. While year one sales were only $30 million, without a competitive response from Gillette, Dollar Shave continued to grow year-by-year, until Unilever recently purchased the brand for $1 billion.

To illustrate, click on the blue ocean brand strategy diagram to zoom in.

Marketing warfare rules for success

- The speed of attack matters. Surprise attacks, but sustained momentum in the market is a competitive advantage.

- Be organized and efficient in your management. To operate at a higher degree of speed, ensure that surprise attacks work without flaw, be mobile enough.

- Focus all your resources to appear bigger and stronger than you are. Focus on the target most likely to quickly act, focus on the messaging most likely to motivate and focus on areas you can win.

- Drawn out dogfights slows down brand growth. Never fight two wars at once.

- Use early wins to keep the momentum going and gain quick positional power you can maintain and defend counter-attacks.

- Execution matters. A quick breakthrough requires creativity in your approach and quality in execution.

- Expect the unexpected. Think it through thoroughly. Map out potential responses by competitors.

- In a red ocean world, you need to own your territory efficiently and ruthlessly beat your competitors.